Barkley Hendricks’s Art: Choosing Not to Center Misery

I chuckled and shook my head as I read a 2016 interview with Artspace editor Karen Rosenberg and Barkley Hendricks. Hendricks was clearly testy in the interview. The very first question set him off, yet Rosenberg didn’t catch on and continued with the same line of questioning.

What was bothering Hendricks? Multiple questions inquiring if politics is central to his work. He interrupts her right away to say, “It’s not the heart. It’s a portion. I’m curious, how much are you aware of my work?

As I read this article, I got the sense he often had to ask interviewers this question because they seemed eager to categorize him as a one-dimensional Black artist, as if everything he did was about expressing “Black rage” or speaking out against injustices.

Although the backdrop of Hendricks’s life (1945-2017) encompasses injustices and global changes from “colored” and “whites only” water fountains during his childhood, assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., during his early 20s, the moon landing, the rise of hip-hop culture, the decolonization of African nations, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the election of Barack Obama, the murder of Trayvon Martin, and the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

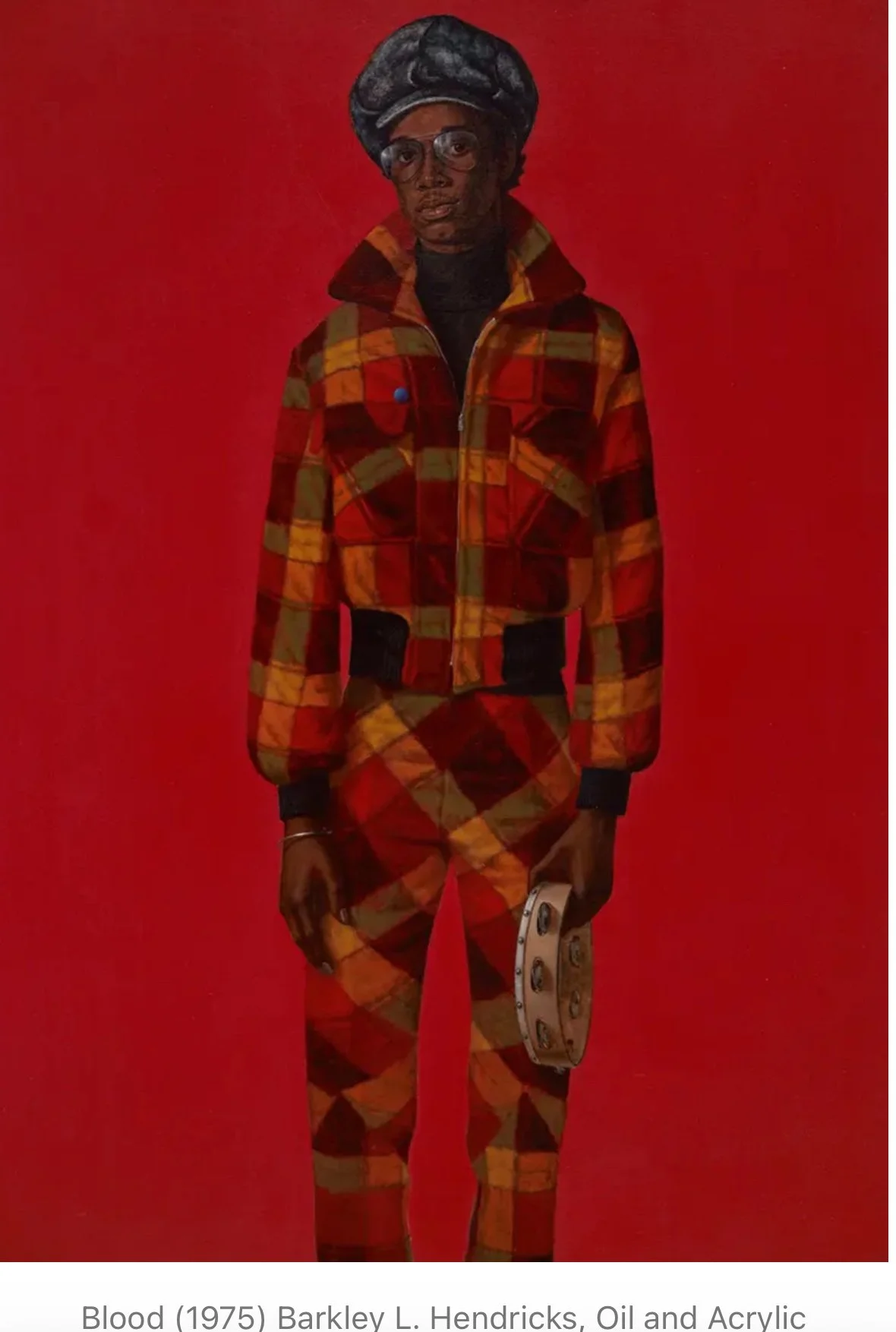

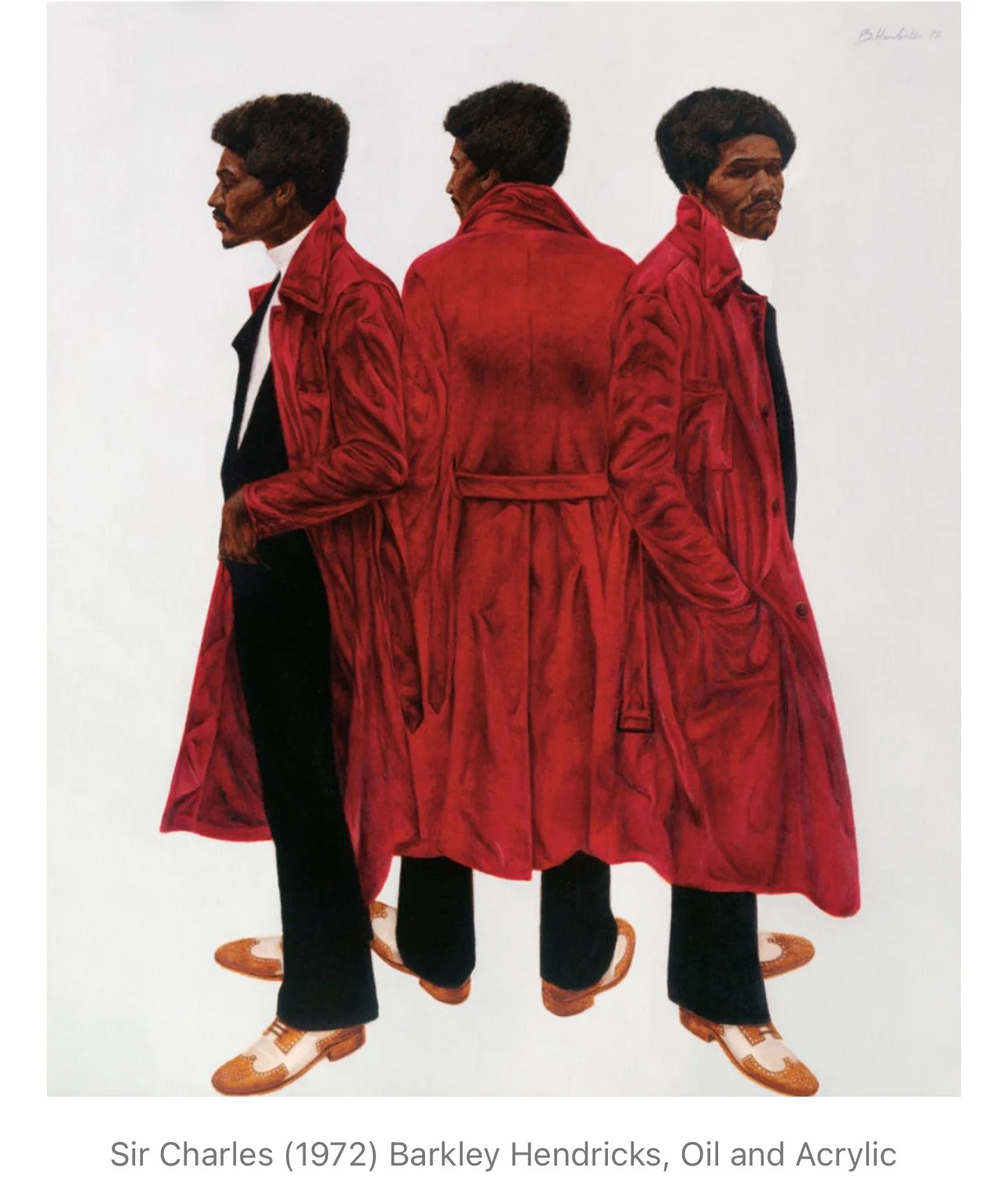

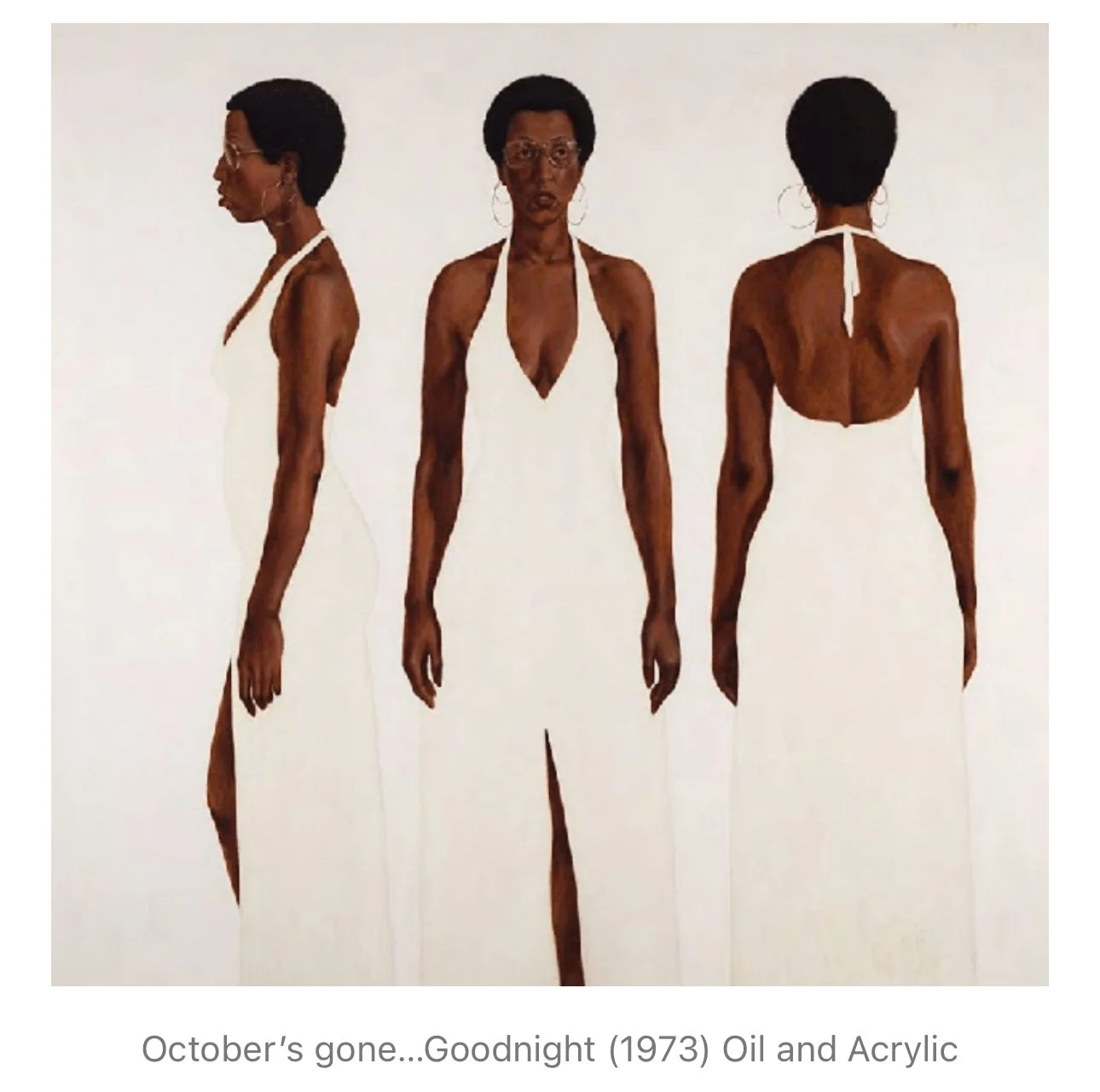

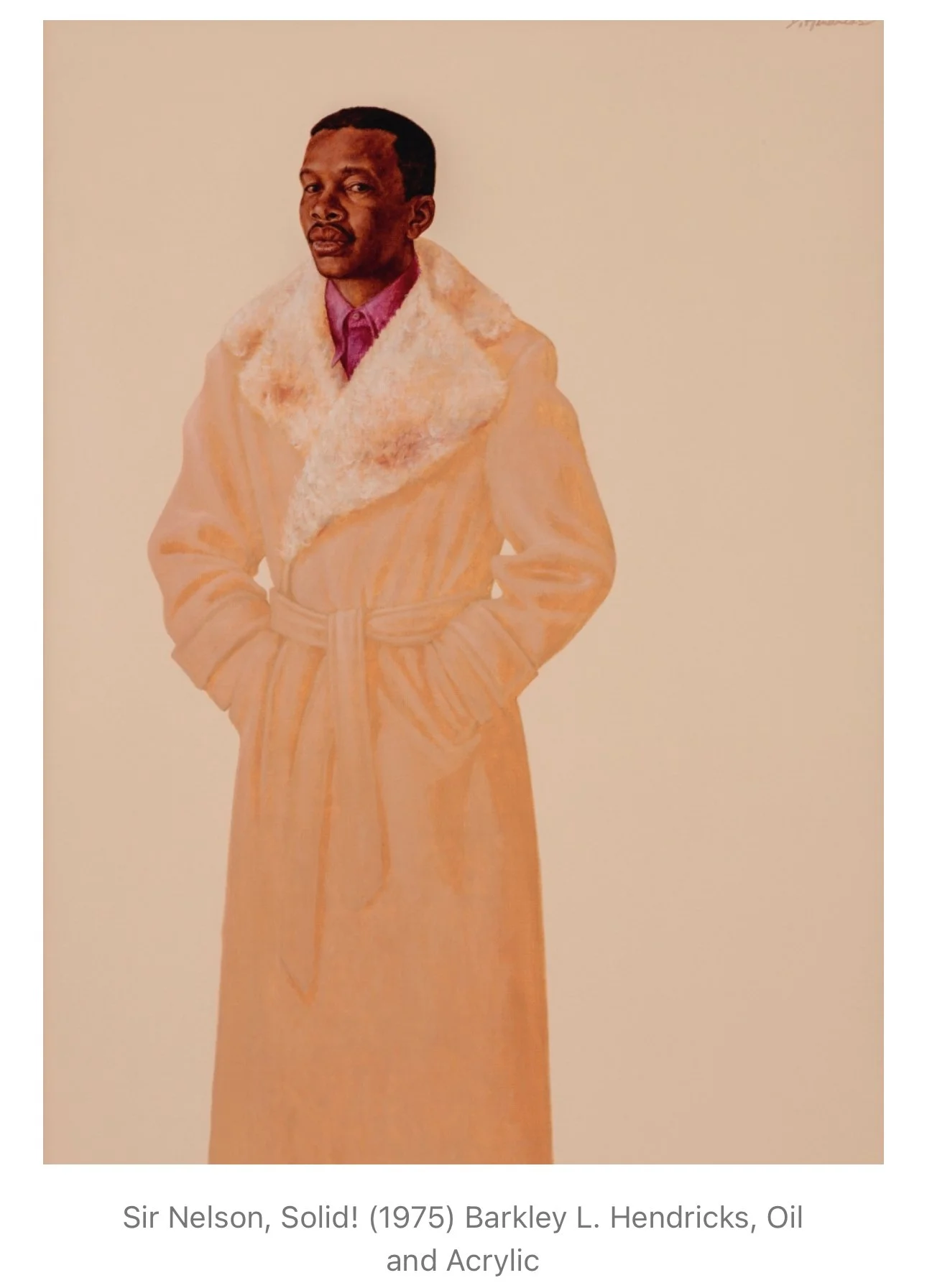

Despite what was happening around the world and in his tough neighborhood in Philly, Hendricks had a life-long guiding principle around his art. Beginning in the late 60s, he intentionally chose not to center misery in his art. In his own words, “I want to deal with the beauty, grandeur, style of my folks. Not the misery.”

He was born and raised in Philadelphia. He graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1967 and went on to earn both his bachelor's and master's degrees at Yale, focusing on photography.

I don’t usually pay much attention to someone’s academic achievements, but I find it impressive that he intentionally chose art when considering his career options after high school, especially at a time when pursuing a “practical” job in the 1960s might have been expected.

He was also a professor at Connecticut College from 1972 until he retired in 2010, teaching drawing, illustration, oil painting, watercolor, and photography.

Hendricks often spoke about the artists who he admired and influenced him, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and Giovanni Battista Moroni, painters often categorized as “old masters.” He encountered their art firsthand in 1966, at the age of 23, when he won a scholarship to travel to the Netherlands, Italy, London, Belgium, Greece, Turkey, Luxembourg and Spain. This European trip had a profound impact on his life and work.

Like most Black and Brown people who encounter Old World art, Hendricks noticed the lack of representation, despite, as he noted, “we were just outside working on the docks, if anyone cared to notice.” Nevertheless, he found tremendous inspiration for European artists.

He was a voracious museum visitor. Upon his return to the States, he decided to focus on portraits of people he knew and those he encountered during his walks around Philly and the world with his camera.

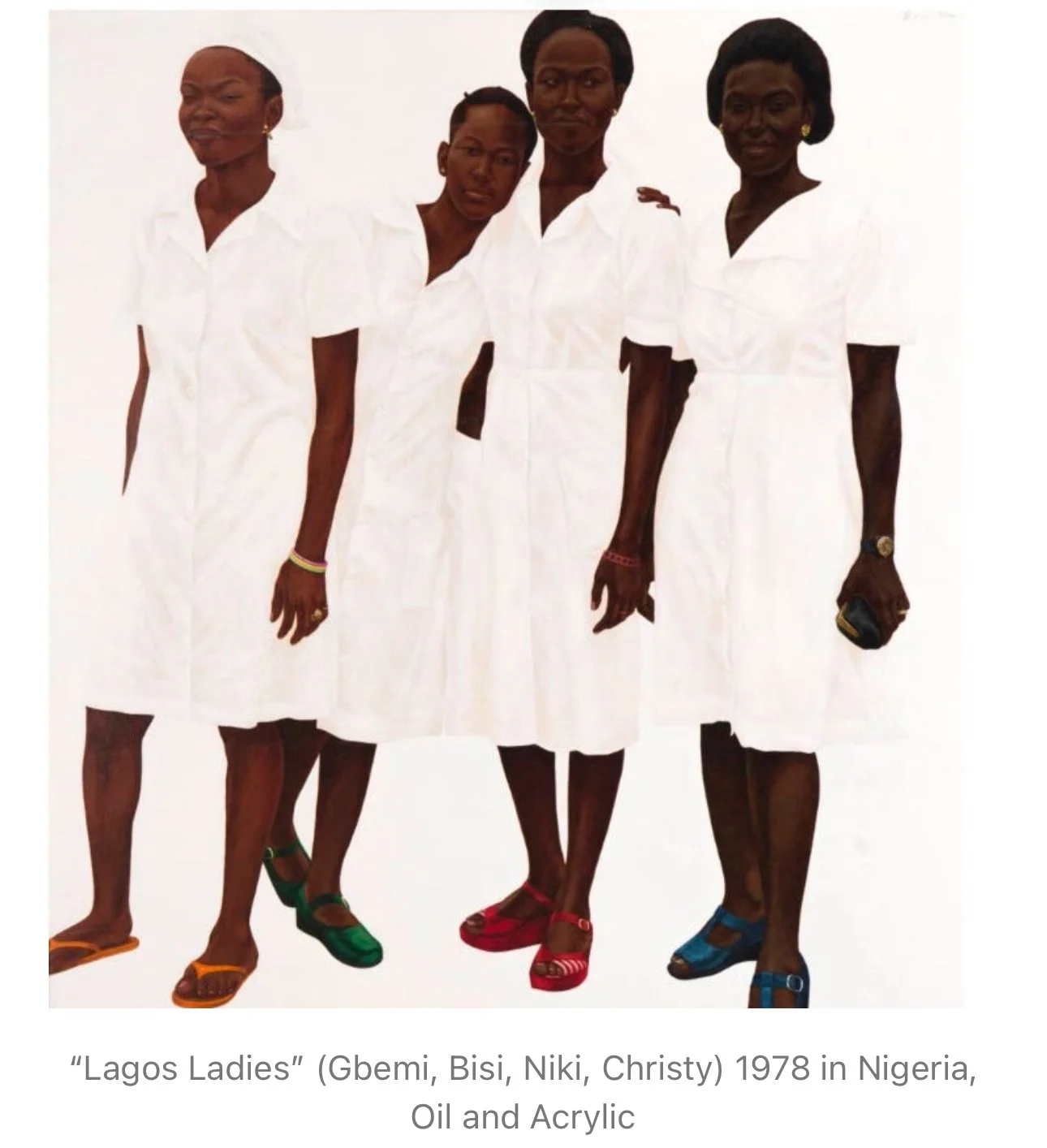

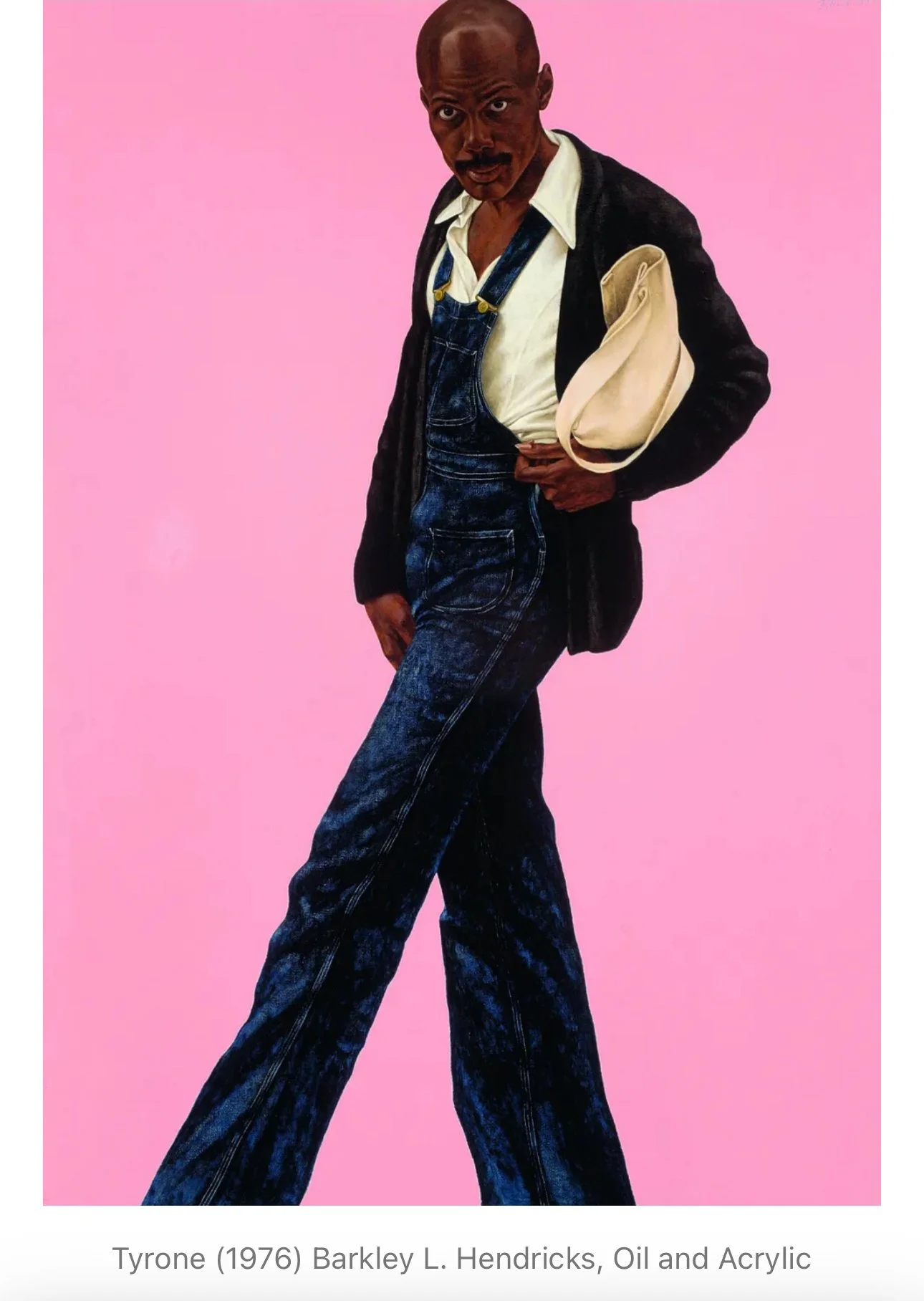

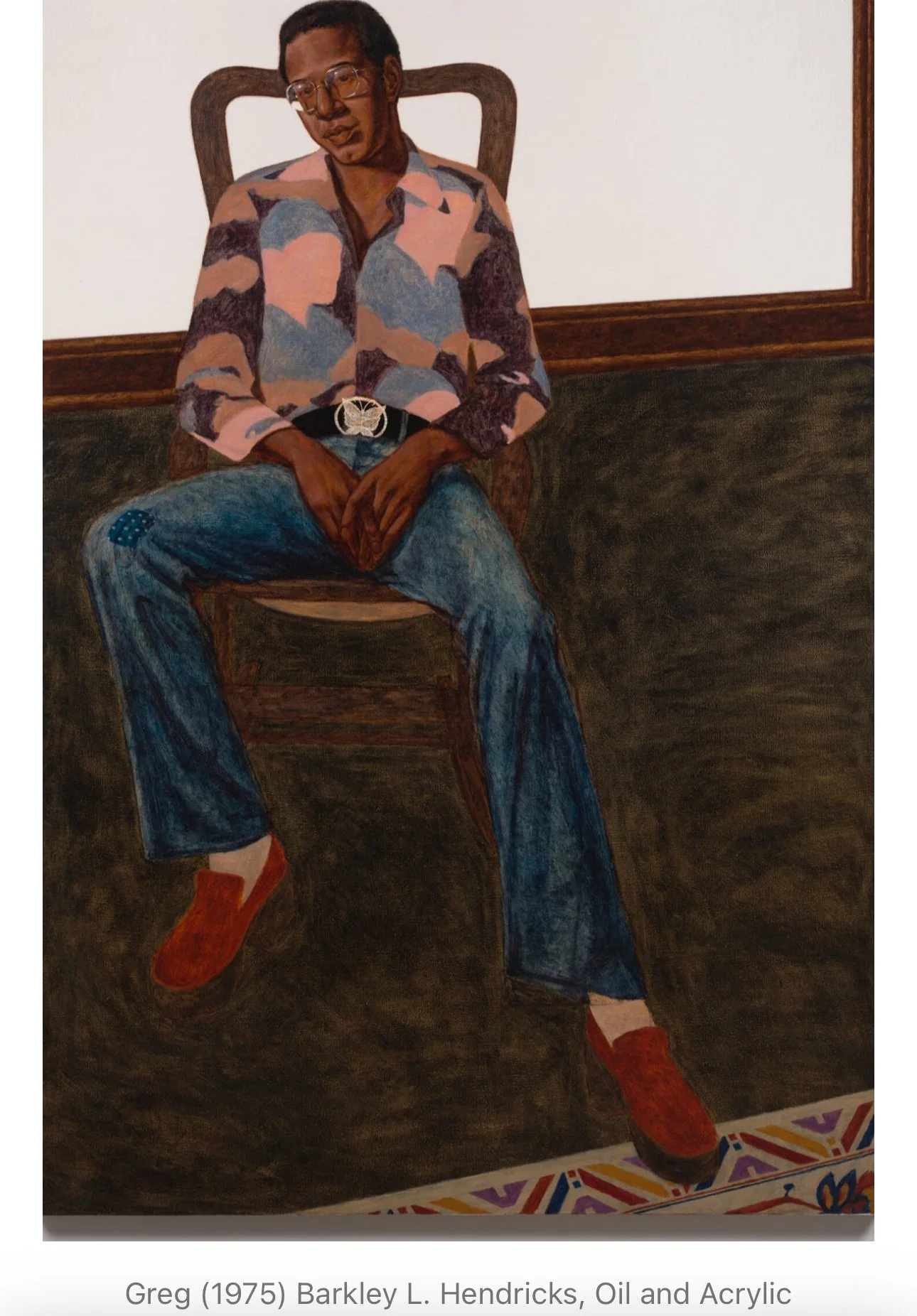

A game-changer in Barkley Hendricks’ work beginning in the late 60s was his decision to eliminate detailed backgrounds and instead use solid, minimal backgrounds, making the figure the ultimate focus.

By intentionally leaving out context clues such as public streets, living rooms, graffiti walls, or cityscapes. He presented his subjects outside of environments that might limit them or feed into stereotypes. This deliberate choice elevated his subjects, allowing them to exist as iconic and grand presences.

Hendricks says his figures are asking the question, “do you see me?” Not the me that is part of a larger group, movement or protest but figures who possess their own unique sense of self, as shown through their style choices.

They are not stand-ins for a larger group or symbols for any particular movement. I find this perspective profoundly powerful and insightful, as it uplifts the individual in a world where groups are so often viewed as monolithic.

Hendricks had been explaining his artistic intentions since the 1960s so you can imagine how annoying it was for him that the Artspace editor then asked if his art is political and in response to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Hendricks’s art was never a reaction to a single movement or a “rage against the machine.” His focus was always on highlighting the individual and their nuanced self.

He often remarked that American culture tends to lack nuance, frequently reducing the world to a binary choice of black and white.

An example of this is Barkley’s multiple paintings of his friend, Jules Taylor. Jules was a black, queer man. They attended Yale together and Taylor died of AIDS in the 80s. Hendricks didn’t see him as a stand in for the AIDS or LGBT movement. He was his funny, stylish, jazz-loving brilliant and iconic friend. Hendricks felt he needed no special, deep-meaning to paint people from his social circles and in his neighborhood.

I got to see Hendricks’s painting of Jules Taylor at the National Gallery of Art in DC. It’s a huge, life-sized painting and you really feel Jules’s presence, individuality and wholeness while taking in the portrait.

At age 72, the year of his death, Hendricks remained steadfast in distancing his work from activist art. Let’s be clear, Barkley wasn’t walking through life with blinders. He spoke openly about being racially profiled and his experiences as a Black man in America. However, he was intentional about creating space between the “noise” of societal issues and his art, preserving the focus on individuality and the personal.

Reflecting on this month’s election, I am noticing that coalitions and movements are fickle, fleeting, and disappointing. I think Barkley Hendricks was on to something focusing on the individual, nuance, locality, and eliminating the “noise” and misery.