Elizabeth Colomba’s Art: Making Invisible Women Visible

This essay is part of my ongoing exploration of art history as a means to educate myself and share my learnings.

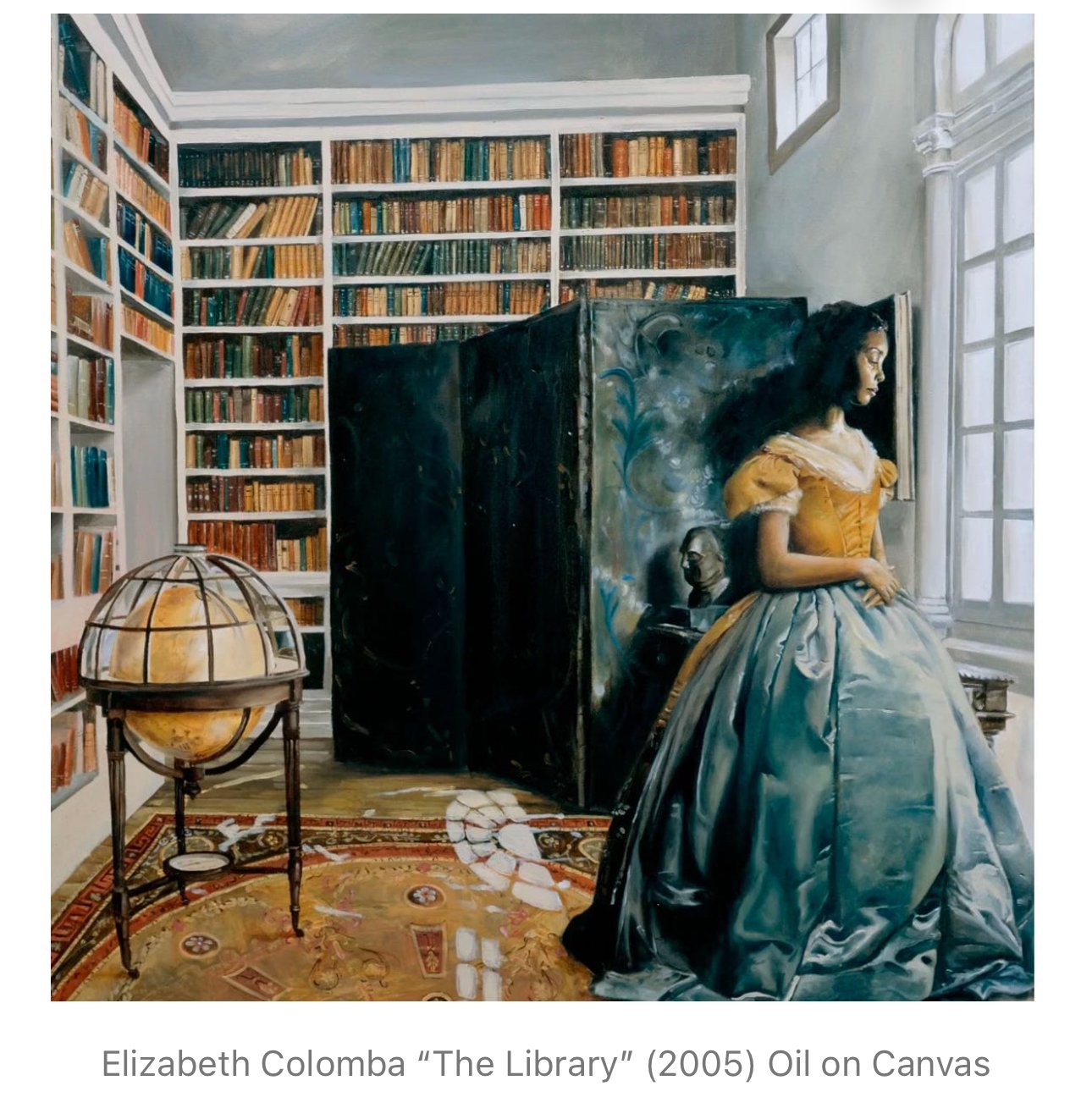

Art has a way of stirring latent feelings, and Elizabeth Colomba's work does exactly that.

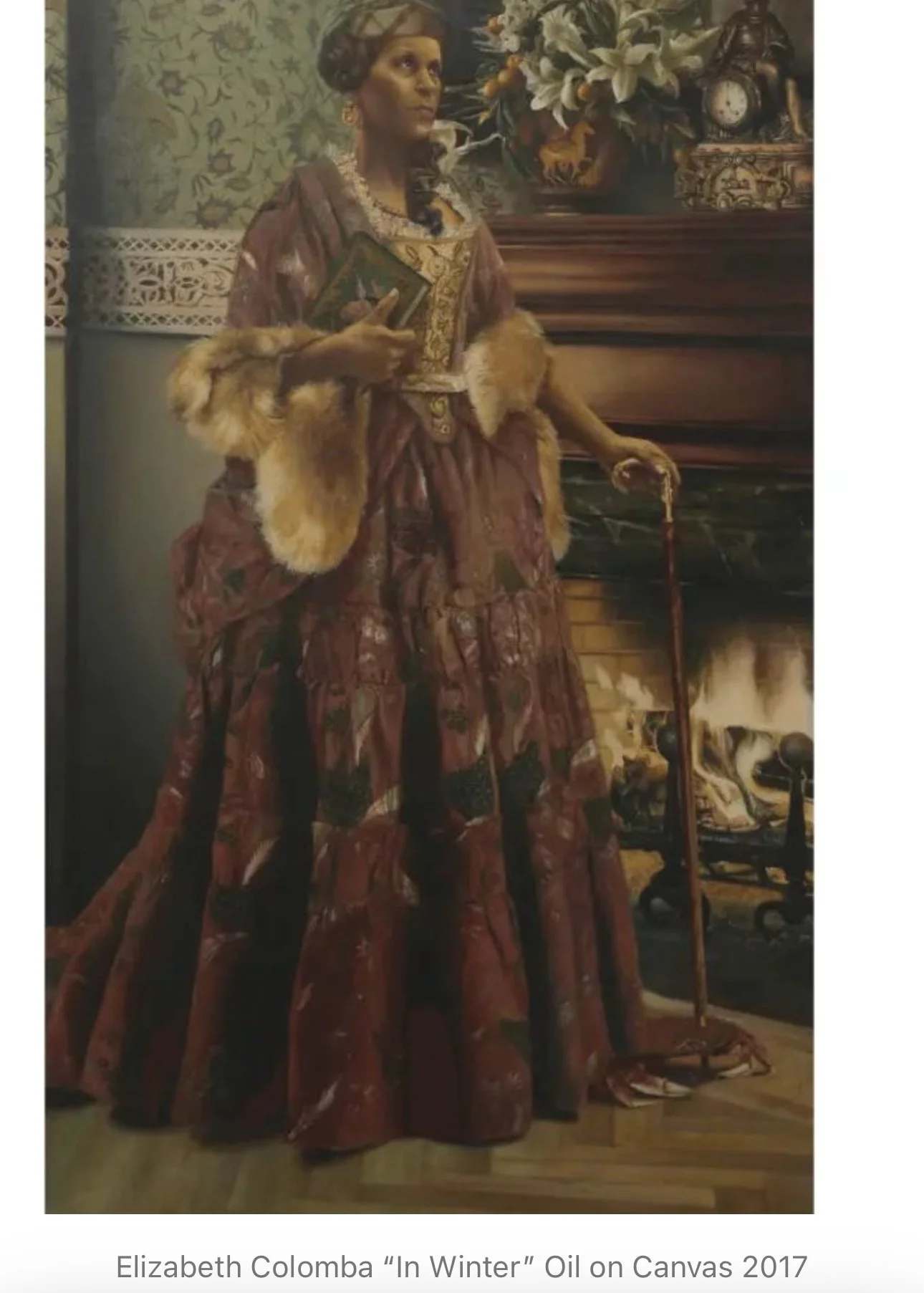

When I first encountered her artwork, I was drawn in. As a vintage lover, sucker for period films and a George Eliot/Bronte sisters avid reader, I liked the rich colors and the time-worn interior spaces depicted in all of Colomba’s work.

Yet, beneath my initial appreciation, I noticed the same unease I experience when watching Bridgerton or seeing people of color in Victorian-era settings.

I don’t think I will be able to completely flesh out why I have both a positive and unsettling reaction, but I will do my best to at least share my initial sentiments and I invite you to share your thoughts.

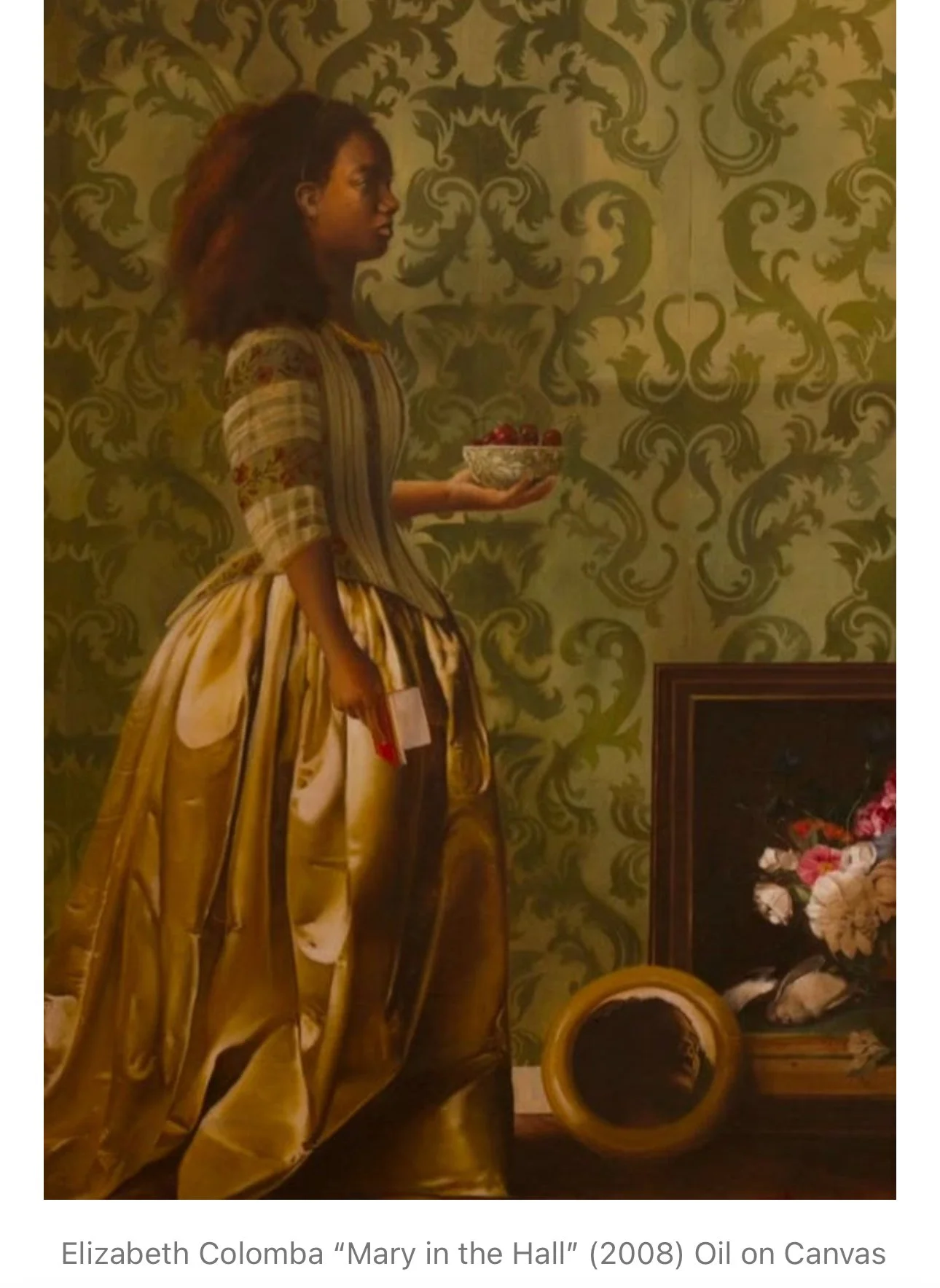

Colomba's artwork is grounded in a mission of visibility and reclamation.

Born in France in 1976 to parents from Martinique, she is a classically trained painter who deliberately centers Black women in historical contexts that have traditionally erased them.

Her work is a direct response to Western European art's historical practice of rendering Black subjects anonymous.

If an artist used a Black model, they typically did not include their names in the title or give them credit for the piece.

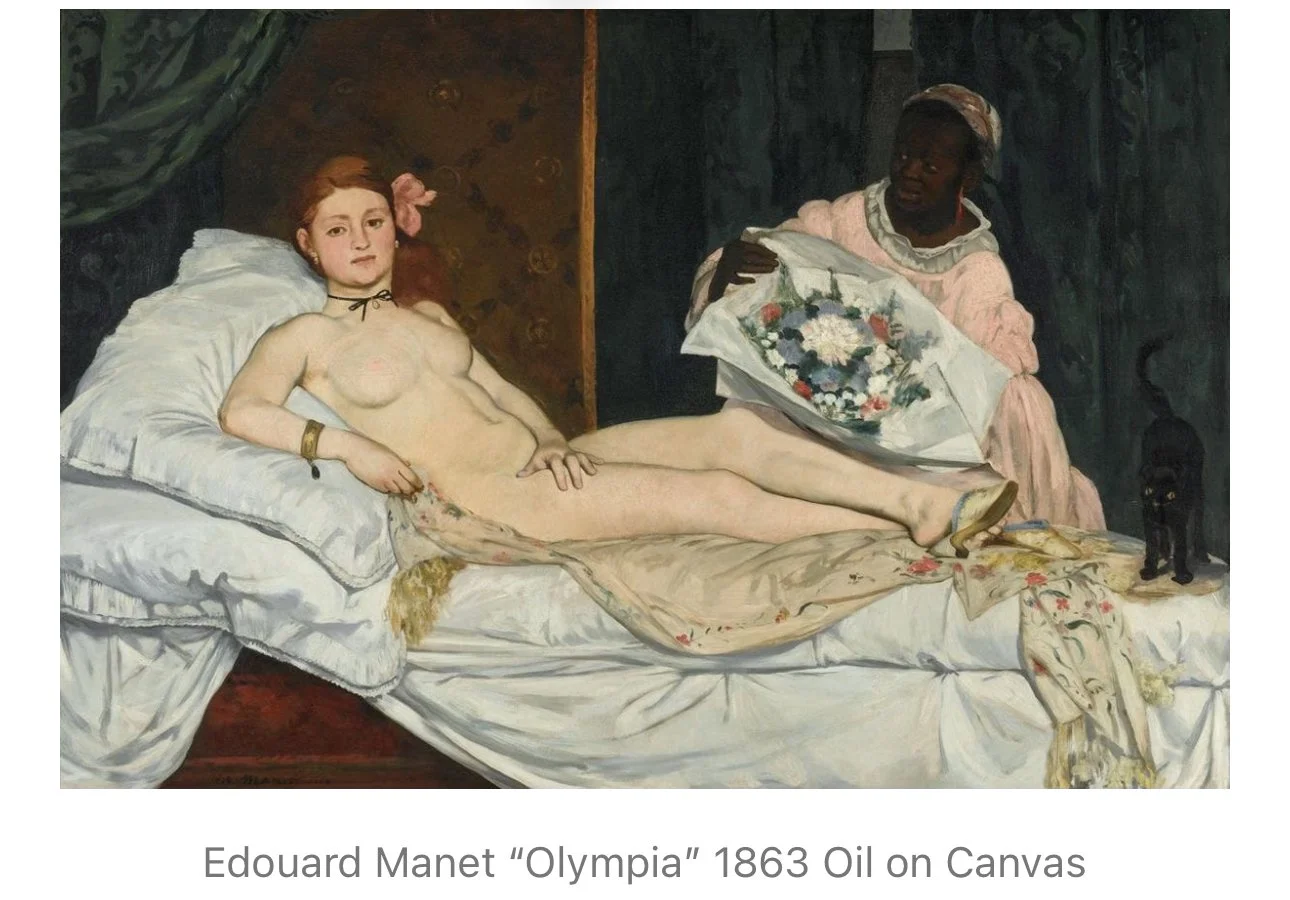

Take, for example, the unnamed Black maid in Édouard Manet's famous painting Olympia.

In his notebooks, Manet referred to her simply as "Laure...très belle négresse" ("Laure...very beautiful negress"), reducing her to a nameless figure despite painting her live and her close proximity to his studio in a vibrant Black Parisian community.

In this particular work below, Colomba reinterprets this historical moment by reimagining Laure not as a cowering servant, but as an independent woman confidently walking to Manet's studio.

By incorporating actual Parisian landmarks near the studio, she invites viewers to walk alongside Laure, to see her not as a background character, but as main character energy in her own story.

"I wish to bend an association of ideas," Colomba states, "so a Black individual in a period setting is no longer synonymous with slave or subservient, and by extension becomes the center of their own tale.”

I think my unease with these paintings also stems from cultural identity and assimilation as expressed through clothing.

Cultural identity is rarely simple, and clothing is never just fabric.

Clothing is not a neutral backdrop. It carries social meaning, reflects status, signifies assimilation, and embodies cultural expectations. Sometimes, it even signals erasure.

Identity itself is a nuanced interplay of internal and external factors that include time/era, place, trends, personal values, individual personality, desires and hopes.

Looking at the clothing in Colomba’s work, I can’t help but to think that prior to their arrival in the West, people of African descent had their own distinct styles of dress with varied symbolic and intricate patterns.

These were rooted in identity, tradition, and utility that is shaped by both creativity and geography. For those living closer to the equator, clothing often countered the heat.

Seeing all the layers, long sleeves, bustles, and waist-cinching contraptions of Victorian-era clothing feels off, overwhelming, beautiful and graceful all at the same time.

It raises questions: To what extent is clothing an expectation or a demand of assimilation?

Is my unease also tied to the guilt that assimilation can happen so quickly, sometimes seamlessly without looking back and that we may even find joy and freedom in stepping into “new shoes?”

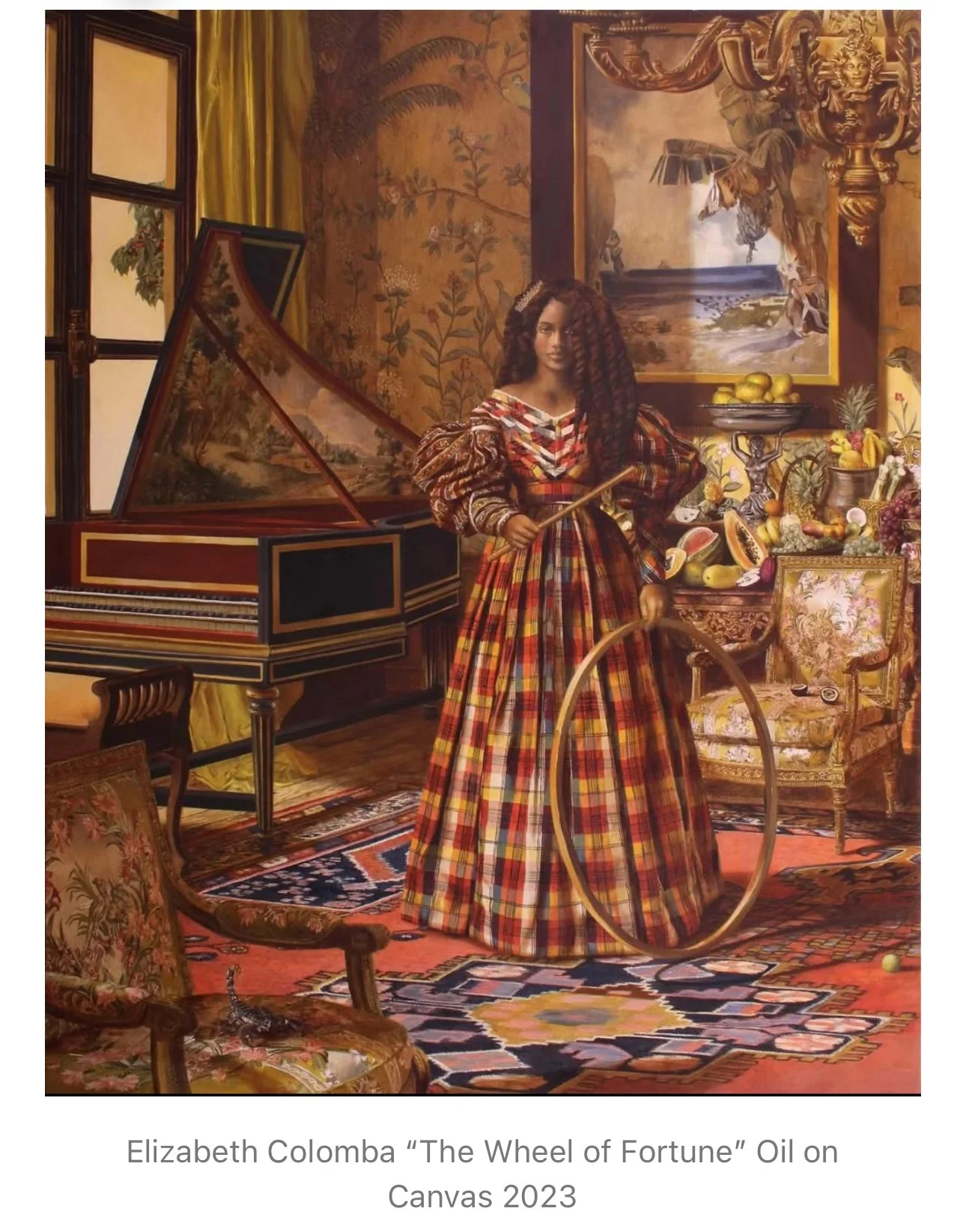

While I feel this dissonance in the clothing and presentation, I wonder if I’m applying too narrow a lens to period pieces, whether in painting or Bridgerton.

Perhaps two narratives can coexist: new identities, adaptation, and assimilation can feel like being boxed in or erased, yet they can also offer freedom, personal agency, and exciting opportunities to recreate new ways of being and living.

What if adopting European dress, mannerisms, and cultural norms offered Laure and others like her a pathway to social mobility?

And what if these women actually enjoyed these adaptations (put their own spin on them like we often do), much like I find myself dressing in Western clothes today rather than in my Ghanaian Ankara pieces?

Maybe this is the crux of it: Colomba’s work challenges me to sit with the tension of identity and assimilation as a constant negotiation, inviting me to hold space for both an appreciation of shifting identities and the discomfort of the dissonance that comes with assimilation.